Originally printed in the March/ April 2009 issue of Afterimage

Posted: June 2, 2009

Reflecting upon documentary photographer Karen Marshall’s work, one cannot help but think about Pieter Breughel’s 1565 painting The Harvesters, located in the European Paintings Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Needless to say, the comparison between Bruegel’s and Marshall’s work is not about “masterworks” but rather intent and context. Among the paintings of religious figures and aristocrats, Breughel’s painting is a seemingly simple and straightforward one—depicting average people going about their daily lives in the late summer months. Some are tending to crops as others are eating and drinking under the shade of a large tree and in the far distance one can make out children playing in the field. This seemingly simple caricature-like painting reveals a class of people often overlooked in the art of its time and place, much like the work of Marshall, which for more than thirty years has predominately captured the everyday life of middle-class America frequently overlooked in contemporary art. While other photographers such as Tina Barney and Sally Mann have addressed teenage adolescence, which is a predominant focus of Marshall’s work in this article, it is her long-term raw anthropological-like style that sets her work apart.

Reflecting upon documentary photographer Karen Marshall’s work, one cannot help but think about Pieter Breughel’s 1565 painting The Harvesters, located in the European Paintings Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Needless to say, the comparison between Bruegel’s and Marshall’s work is not about “masterworks” but rather intent and context. Among the paintings of religious figures and aristocrats, Breughel’s painting is a seemingly simple and straightforward one—depicting average people going about their daily lives in the late summer months. Some are tending to crops as others are eating and drinking under the shade of a large tree and in the far distance one can make out children playing in the field. This seemingly simple caricature-like painting reveals a class of people often overlooked in the art of its time and place, much like the work of Marshall, which for more than thirty years has predominately captured the everyday life of middle-class America frequently overlooked in contemporary art. While other photographers such as Tina Barney and Sally Mann have addressed teenage adolescence, which is a predominant focus of Marshall’s work in this article, it is her long-term raw anthropological-like style that sets her work apart.

Departing from street photography in the early 1980s and engaging in more intimate investigations of groups such as middle-class teenage girls living in New York City, Marshall’s most driven project to date is her series entitled “Between Girls” (1985–2005). A long-term study, this collection of photographs, audio recordings, and films reveals the changing lives of young, urban, middle-class women as they age from sixteen years old to thirty-nine. Marshall states, “I was tired of photographing on the streets … I had no interest in these much broader—no relationship—type of ways of looking at culture … I was interested in the photograph’s ability to convey psychological ideas. And I wanted to photograph the familiar. I wanted to photograph literally inside people’s lives.”(1)

After a number of false starts, Marshall was introduced to sixteen-year-old Molly Brover, who lived on the upper west side of Manhattan along with her group of friends. At first Marshall admits that there was a bit of posing; however, after a while, “they forgot me. They were so relaxed in front of the camera. And they sort of understood what I was trying to do … [T]here was no self consciousness.”(2)

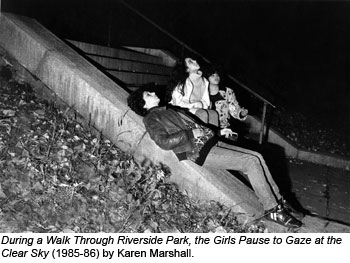

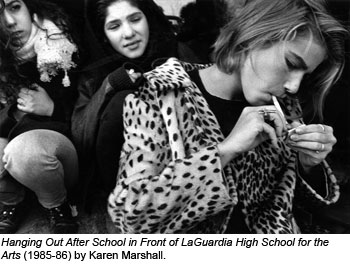

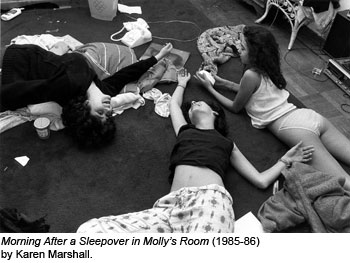

The images shot with a 35mm camera tend to be grainy and maintain earlier adopted street photography characteristics such as unique angles of vision, interesting juxtapositions, and strong graphic patterns. Nevertheless, the remarkable element of this series of black-and-white photographs is that there is an imagined audio quality to the images. For example, in the photograph entitled Morning After a Sleepover in Molly’s Room (1985–86), the viewer has a bird’s-eye view of three young girls lying on the floor engaged in a slumber party conversation—laughing and possibly gossiping. The girls have strategically placed a phone nearby as they might call a friend or dare one another to call that “hot guy” in class or one of their crushes. The viewer is not privy to the actual conversation, but one’s internal sounds of memory may bring back the many recollections of adolescence. The youth as rebel is apparent in the striking image Hanging Out After School in Front of LaGuardia High School for the Arts (1985–86), as the girl in the foreground lights up a cigarette while her friends look on with a combination of curiosity, nervousness, and envy. The hopeful, innocent, and almost cliché-like image of three girls staring up at the stars on a brisk night, During a Walk Through Riverside Park, The Girls Pause to Gaze at the Clear Sky (1985–86) personifies the dreams, aspirations, and fears of teenagers as they cross the boundaries from childhood to adulthood.

The images shot with a 35mm camera tend to be grainy and maintain earlier adopted street photography characteristics such as unique angles of vision, interesting juxtapositions, and strong graphic patterns. Nevertheless, the remarkable element of this series of black-and-white photographs is that there is an imagined audio quality to the images. For example, in the photograph entitled Morning After a Sleepover in Molly’s Room (1985–86), the viewer has a bird’s-eye view of three young girls lying on the floor engaged in a slumber party conversation—laughing and possibly gossiping. The girls have strategically placed a phone nearby as they might call a friend or dare one another to call that “hot guy” in class or one of their crushes. The viewer is not privy to the actual conversation, but one’s internal sounds of memory may bring back the many recollections of adolescence. The youth as rebel is apparent in the striking image Hanging Out After School in Front of LaGuardia High School for the Arts (1985–86), as the girl in the foreground lights up a cigarette while her friends look on with a combination of curiosity, nervousness, and envy. The hopeful, innocent, and almost cliché-like image of three girls staring up at the stars on a brisk night, During a Walk Through Riverside Park, The Girls Pause to Gaze at the Clear Sky (1985–86) personifies the dreams, aspirations, and fears of teenagers as they cross the boundaries from childhood to adulthood.

With a set of photographs such as the ones mentioned above depicting teenage girls’ adolescence, a narrative might have been found through the editing process and the project may have reached its conclusion. However in 1986, the life of the central character in Marshall’s work, Molly Brover, had abruptly ended when a car hit her. In an email interview, Marshall stated, “Her dark theatrical style along with her poetic and scattered energy drew my lens easily to her, providing me with a natural and compelling cinematic teenager. Her enthusiasm for my project provided me with the dialogue I was looking to establish—that of the emotional interior world that groups of girls can experience together as teenagers.”(3)

Marshall continued with the investigation for another twenty-two years and recorded the lives of these women as they approached and crossed different stages of their lives. In an interview with this author, Marshall commented:

All of a sudden, Molly, who had sort of opened a gate for me, was gone … [W]hat occurred to me was that Molly’s death was a metaphor for a lot of things … And I realized that it’s like they’re really excited about becoming adults, but they’re also profoundly mourning their childhood. It’s also a … metaphor about photography, that it’s this distillation of time. It’s a [fraction]of a second, and the gesture was there and then it’s gone."(4)

The post-Brover photographs appear more quiet and sedate rather than action-oriented—reflecting on the inward. Even in the more celebratory images of marriage and birth that Marshall has recorded of this group of women, there is a psychological notion of passage and quietness evident in Marshall’s framing and selection of imagery within these later images.

As adolescence has been a Petri dish for shaping her subjects’ identities, Marshall’s interest in photography began when she was a teenager at a summer arts camp. She comments, “I obsessively knew that I wanted to do photography. And at the time, which was the mid-1970s, there were very few liberal arts schools that had solid photography departments. There were certainly the art institutes, but I really wanted a liberal arts education.”(5) Hampshire College proved to be an appropriate fit for her with its documentary-oriented program where she studied under such notable photographers as Jerome Liebling and Elaine Mayes. In addition, at the San Francisco Art Institute she studied under John Collier Jr., who wrote Visual Anthropology (1986). After graduating from college, she received a certificate from the International Center for Photography in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography where she now teaches. Marshall, who also completed her MFA in 2008 with a focus in New Media from the Transart Institute at Danube University Krems in Austria, believes that “narrative photography has the opportunity to take advantage of complimentary media without diluting the power of a well-executed photograph.”(6)

Through the years, Marshall has recorded her “Between Girls” subjects with various media from still photography to audio recordings to video in order to capture and reflect an important identity-forming moment in their lives—their adolescence. Using diverse media allows for a potentially broad-based and comprehensive investigation into understanding the complex social dynamics of adolescent girls. All of the “Between Girls” participants agree that their adolescent friendships played an important role in the shaping of their identities as adults. As one member of the group reflects in a video, “My friends have always been my family and I think we helped raise each other in a way that our parents didn’t and weren’t present in that way.”(7)

While Marshall has shown aspects of the “Between Girls” project in exhibitions and though the project has taken different forms, she has had difficulty resolving the final presentation of this project. But she has plans to finalize it as an installation—combining, text, audio, video, and photography that will engage the viewer in a poetic understanding of adolescence. Her struggle with the process of this project is a metaphor for the paradigm shift in documentary photography over the past two decades, as its primary staple of income—the magazine photo essay—has dissipated and the concept of new media has been introduced. Conceptually and materially, the notion of documentary photography is in a state of flux. Marshall asserts that contemporary documentary photography “is really confused. There’s an attitude out there that it is dead … [T]here are a lot of curators, editors, [and] writers who would say it’s dead. I think that what they mean by that, which I don’t disagree with, is that there are certain types of work that used to move us—our hearts—greatly, that are an old genre.”(8)

While Marshall has shown aspects of the “Between Girls” project in exhibitions and though the project has taken different forms, she has had difficulty resolving the final presentation of this project. But she has plans to finalize it as an installation—combining, text, audio, video, and photography that will engage the viewer in a poetic understanding of adolescence. Her struggle with the process of this project is a metaphor for the paradigm shift in documentary photography over the past two decades, as its primary staple of income—the magazine photo essay—has dissipated and the concept of new media has been introduced. Conceptually and materially, the notion of documentary photography is in a state of flux. Marshall asserts that contemporary documentary photography “is really confused. There’s an attitude out there that it is dead … [T]here are a lot of curators, editors, [and] writers who would say it’s dead. I think that what they mean by that, which I don’t disagree with, is that there are certain types of work that used to move us—our hearts—greatly, that are an old genre.”(8)

Even though documentary photography has found patronage from the commercial art gallery, current mainstream contemporary art does not mesh well with documentary photography as it tends to be theoretical, formal, and self-reflective using a specific language that is at times inaccessible to a general public. Documentary photography, on the other hand, tends to have qualities that focus on issues of accessibility, psychology, and subjective truth. Marshall herself defines documentary photography as, “an in-depth investigation of a culture, a people or idea—that’s a social or cultural landscape.”(9)

Metaphorically, contemporary documentary photography is much like The Harvesters being situated among artworks depicting aristocrats and religious icons. Developing appropriate venues in a time when contemporary printed newspapers and mainstream galleries do not suffice for such an investigation is important, so that contemporary documentary photography can once again be a viable and healthy partner in the contemporary visual culture as it gives us an understanding and reaffirmation of who and what we are as human beings.

In addition to the book form, it may be possible that through new media and organizations that are sensitive to documentary photography, as well as non-profit galleries and museums, that this medium can grow conceptually and artistically in ways that have not been imagined, enabling projects like Marshall’s to thrive.

>> For more information on Karen Marshall, please visit her website: www.karenmarshallphoto.com

NOTES

1. Author interview with Karen Marshall on August 13, 2008.

2. Ibid.

3. Author email interview with Karen Marshall on December 8, 2008.

4. Author interview (August 13, 2008), Ibid.

5. Author interview (August 13, 2008), Ibid.

6. Author email interview with Karen Marshall on December 15, 2008.

7. Video clip (2007–08) provided by Karen Marshall.

8. Author interview (August 13, 2008), Ibid.

9. Author interview (August 13, 2008), Ibid.