Originally published in the Journal for Arts in Society (Volume 3, Number 3, 2008)

Posted January 28, 2009

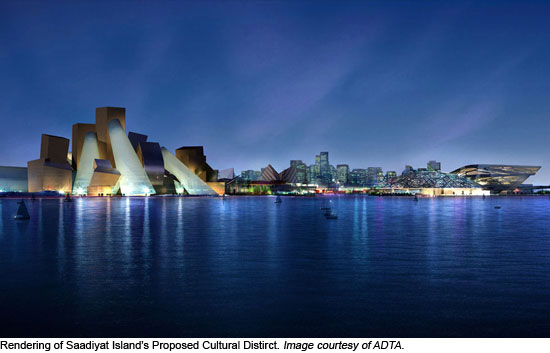

Faced with the challenges of globalization, which many believe creates homogeneity and loss of uniqueness and identity, the emirate of Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates is in the process of positioning itself as an international tourist destination with an estimated $27 billion dollar development project on Saadiyat Island that includes museums, hotels, resorts, golf courses and housing that could accommodate more than 125,000 residents. An important component of Saadiyat Island is its Cultural District, which will include the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the Performing Arts Centre, the Maritime Museum and the Sheikh Zayed National Museum. It appears that a major goal of this district is to jump-start cultural tourism and to aid in the development of the local economy. Providing an overview of Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District, this paper analyzes and critiques museum initiatives that were designed in part to develop the local economy and reflects upon the role of education within a museum context.

While some may consider museums as cobwebbed-filled repositories of cultural gems and/or junk, these institutions provide life-long learning opportunities, attract tourists and, in many cases, play a vital role in the economic success of a city. Capitalizing on the successes of other cities that have used star architects to design trophy buildings, the Saadiyat Island developers have employed Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid and Tadao Ando to create memorable buildings that entice visitors to see not only the quality exhibitions that the Louvre and Guggenheim brands have been known to deliver but also the architectural wonders that house these promising shows.

In an effort to rely less on its oil resources as a primary source of income, Abu Dhabi is working to diversify and stimulate its economic growth through tourism development. In 2004, the Abu Dhabi Tourism Authority (ADTA) actively began pursuing the development of Saadiyat Island, an island 500 meters off of the coast of Abu Dhabi, to create an international tourist destination. One of the main components of this project is the Cultural District, which ADTA is developing to be “a destination everyone in the world of art and culture would have to visit, annually and more than once, by building a series of permanent institutions—museums, performing art centers, exhibition halls, educational institutions in the arts—that through its collections, architecture and programs will become one of the greatest concentrations of cultural experience anywhere in the world” (ADTA, 2007b).

His Highness Sheikh Mohammad bin Zayed, the Crown Prince of the Emirate Abu Dhabi, reaffirms this goal by stating, “The aim of Saadiyat Island must be to create a cultural asset for the world. A gateway and beacon for cultural experience and exchange. Culture crosses all boundaries and therefore Saadiyat will belong to the people of the UAE, the greater Middle East and the world at large” (ADTA, 2007a).

In 2005, the ADTA and the Tourism Development Investment Corporation (TDIC) hired the New York City-based Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation to develop the “conceptual stage” of Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District project. The Guggenheim’s role has been to help develop and refine the master plan for the Cultural District and assist with the recruitment of internationally recognized architects. In an August 6, 2007 Newsweek article, Thomas Krens, the Director of the Guggenheim Foundation, commented about his involvement with the Saadiyat Island project:

The Guggenheim signed an agreement to develop the master plan for the cultural district, which called out [for] a modern and contemporary art museum, a classic art museum, a national museum, a maritime museum, a performing arts center and a biennale pavilion.

My driving concept was to create a critical mass that by definition would be—rather aggressively—the greatest concentration of contemporary cultural resources in the world (Krieger, 2007).

Although Thomas Krens has played a considerable role in linking architects and fine-tuning the master plan for Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District, he states, “most decisions have to take place with approval of the rulers. Sheikh Mohammed is the crown prince, and this is very much a Sheikh Mohammed project” (Krieger, 2007).

In order to evaluate the viability of such an undertaking, the developers researched and analyzed the economic impact of such contemporary cultural developments and/or expansion projects as the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain; the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, USA; the Cultural Park, Chicago, Illinois, USA; and the Tate Modern, London, England. From the case studies presented in the Saadiyat Island Cultural Exhibition at Emirates Palace Hotel in Abu Dhabi, it would appear that economic impact is one of the most important aspects of the development of the Cultural District.

The impact of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is often cited as an example of culture being a primary factor in the economic rejuvenation of a city. Much like the Abu Dhabi Tourist Authority (ADTA), the Basque administration in Spain had significant funds for a revitalization plan that intended to strengthen its economy through tourism. While the Basque administration brought both the capital and operating support to their initiative, the Guggenheim Foundation agreed to manage the museum and offer curatorial and acquisition support (Skylakakis, 2005). According to the agreement, the museum would host five or six exhibitions of Guggenheim art collections a year, as well as mount its own locally curated shows (Skylakakis, 2005). With the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the city of Bilbao has marketed itself as a weekend destination for Spanish visitors and/or as an additional stopover for international tourists (Plaza, 2006). The result has been a well-documented success: the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao has reported a 12.8 percent average annual return on investment and 9.2 million visitors from 1998-2006 (ADTA, 2007b).

In order to recreate this success, the ADTA has entered into a similar agreement with the Guggenheim Foundation. Tourism Development and Investment Company (TDIC), an independent company of ADTA, will own the museum, while the Guggenheim Foundation will create and manage the museum’s programs including collection development, exhibitions and educational projects. (Guggenheim, 2006). For many, this may be considered a formula for success, but not all museum development and expansion plans have panned out. When the Milwaukee Art Museum’s new wing designed by Santiago Calatrava opened in 2001, the attendance was lower than anticipated; with the Royal Amouries Museum in Leeds, studies projected 1.3 million visitors, although attendance was one-tenth that number—below 200,000 a year (Plaza, 2006). Additionally, even though the Guggenheim Foundation oversees four museums in New York, Venice, Berlin and Bilbao under the helm of Thomas Krens, other Guggenheim Foundation projects have not been successful. For example, the Guggenheim Soho in New York City quietly closed its doors in 1992 after nine years of operation, and on May 11, 2008 the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas shut down after seven years of operation (Guggenheim, 2008). In addition, other Guggenheim ventures never materialized, such as the plans to build in Taiwan, Rio de Janeiro, Singapore and St. Petersburg.

The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MassMoCA), a brainchild of Thomas Krens in the mid-1980s located in North Adams, Massachusetts, has been touted as a success in economic regeneration by converting a former textile-printing mill into the largest contemporary art facility in America—causing an upsurge in the local economy. However, while visiting MassMoCA in July 2007, this author found many storefronts still empty in North Adams and a few going-out-of-business signs in shop windows. In an interview with this author, Katherine Myers, Director of Marketing and Public Relations at MassMoCA, remarked, “Our priority is not education. It is economic development. We are interested in getting people in the doors.” Nevertheless, a woman working at a local pizza shop said to this author, “I haven’t noticed much difference in the local economy [since the opening of MassMoCA], but my child who is in second grade loves it there.”

This begs one to question: is there more to a museum than economic regeneration for a city? ICOM, the International Council of Museums, defines a museum as a “non-profit making, permanent institution in the service of society and of its development, and open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits, for purposes of study, education and enjoyment, material evidence of people and their environment” (International Council of Museums, n.d.). As a result, the economic and identity factors that many urban planners, museum and marketing directors as well as city officials use to sell a museum development or expansion project should be seen as a by-product for a job well done by an education institution or a rationale for the importance of museums in a city rather than its primary motivation.

While the museum is often touted as a device for economic regeneration in many parts of the world, institutions with international brand names are benefiting the most. In a 2005 New York Times article, Diane Vogel wrote, “There are financial advantages to opening Guggenheims around the world. Cities that approach the Guggenheim about building a museum can expect to spend $150 million to $200 million” (Vogel, 2005).

Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, stated, “Museums are growing for a lot of different reasons. They’re growing because they want a bigger cafeteria, a bigger shop. Or, they want to become a tourist attraction: They want a piece of architecture like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, that will, they feel, be their Eiffel Tower, their destination building” (de Montebello, 2007).

Because such examples as the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Tate Modern and Museum of Modern Art present many of the economic factors that demonstrate how a museum can benefit a city, it can be easy to rest on the laurels of how museums contribute to the local economy. However, uncontrollable external circumstances can alter the fate of a museum. Placing an economic value on a museum and measuring success by attendance figures are dangerous indicators, and the role of a museum as an education institution can be easily compromised during difficult economic times. A museum’s mission must be its directive; the economic impact of tourist dollars, attendance numbers and blockbuster shows should not be seen as the sole measures of success.

Although the potential economic return of museums—such as employment, tax revenue and spending as well as the draw of potential employers to a specific region—are very lucrative to many investors, government officials and urban planners, other instrumental or measurable yields have been overlooked in these studies, such as the educational and social benefits that come with quality exhibitions and museum education programs. Additionally, in many museum economic impact studies, the intrinsic benefits of museums are often taken for granted. While they are the primary motivations for people to visit museums, these overlooked benefits—including pleasure, expanded capacity for empathy, cognitive growth and social interaction—“have been downplayed with an increasingly output-orientated, quantitative approach to public sector management” (McCarthy, Ondaatje, Zakaras, Brooks, 2004).

In addition, economic impact studies can marginalize other arts and cultural organizations because their role may not be perceived as greatly beneficial to the overall economy. Nevertheless, these institutions may play an integral part in the local arts and cultural infrastructure by offering alternative presentations and exhibitions as well as nurturing talent.

A quote by Sheikh Zayed Bin Sulatan Al Nahyan prominently placed in the Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District exhibition reads, "The real wealth for a country is not its material wealth; it is its people. They are the real strength from which we draw pride and the trees from which we receive shade. It is our firm conviction in this reality, that directs us to put all efforts in educating the people" (ADTA, 2007b). With this in mind, it might be of interest to consider the main value of the museum not just as “a destination that everyone in the world of art and culture would visit regularly” but a place where UAE nationals, expatriates and tourists can learn and be inspired. In addition, by connecting with the local school community and offering school-specific programs that would enhance the local curriculum, it would inevitably strengthen public education. For example, if it is not already in the plans, the Louvre Abu Dhabi should not only be a place that preserves relics and educates its visitors on the history of other parts of the world, but it should be a place where archeologically significant artifacts from the UAE and the region can be collected, preserved and used as resource to learn about the area’s past.

In a Spiegel Online March 27, 2008 interview, Krens states that the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will be a museum of global contemporary art—having the “same emphasis for China, Central Asia, India, Africa, Russia, Europe and America.” It will be interesting to see how the Guggenheim will curate and disseminate information with this approach, as most museums have a certain agenda or approach for constructing knowledge with the objects that they collect. For example, in 1792 the French Revolutionary government opened a public museum, now known as the Louvre, that was designed as a pedagogical tool to further nation building. Its aim was to cultivate modern citizens who were civilized and patriotic (Marstine, 2005).

Rather than have cultural institutions working independently like many in the United States do, the United Arab Emirates might find it in its national interest to create an entity modeled after the Ministry of Culture in France, which oversees the French national museums and monuments as well as promotes and protects the arts in France and abroad. Sharjah already has 17 museums, a biennial and was named the 1998 cultural capital of the Arab world by UNESCO. On March 27, 2008, the Gulf News reported that Dubai is developing its own cultural district with 10 museums, nine libraries, 13 theatres, an opera house, galleries, arts and culture institutes and workshops for artists (Gulf News, 2008).

While competition among the Emirates can be benevolent, it would be in the best interest if the UAE’s emirates would not compete with each other regarding their cultural resources, but instead work in tandem with each other, inspiring international visitors and local citizens to visit the cultural institutions that each of the emirates has or is developing. This would make the UAE a place of even greater cultural significance.

REFERENCES

ADTA. (2007 January 31a) Abu Dhabi Commissions World’s Top Architects for Museum and Performing Arts Centre Designs. Abu Dhabi: ADTA.

ADTA. (2007b) Saadiyat Island Cultural District Exhibition. Abu Dhabi: Emirates Palace.

De Montebello, Phillipe. (2007 October 7). Montebello: The Ability to Manage Must Increase, Too. Washington Post. Retrieved on October 12, 2007.

Gulf News Staff Report. (2008 March 27) Initiative to Combine ‘Past and Present.’ Gulf News. Retrieved from the Web on March 28, 2008.

Guggenheim Museum. (2006 July 8 ) Abu Dhabi to Build Gehry-Designed Guggenheim Museum. New York: Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved from the Web onAugust 12, 2007.

Guggenheim Museum. (2008 April 9) Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas Concludes Seven-Year Residency at the Venetian-Resort-Hotel-Casino. New York: Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved from the Web on April 12, 2008.

International Council of Museums (n.d.) ICOM Definition of a Museum. Retrieved from the Web on September 15, 2007.

Krieger, Zvika. (2007 August 6) I’m Not a Service Company. Newsweek International Edition Web Exclusive. Retrieved from the Web on August 12, 2007.

Marstine, Janet Ed. (2005) New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley Blackwell.

McCarthy, K., Ondaatje, E., Zakaras, L., and Brooks, A., (2004) Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the Debate About the Benefits of the Arts. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from the Web on September 15, 2007.

Plaza, Betriz. (2006) The Return on Investment of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, June 2006, 452-467.

Skylakakis, Stefanos. (2005) The Vision of a Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Cambridge: Harvard Design School. Retrieved from the Web on August 9, 2007.

Vogel, Carol. (2005 April 27) A Museum Visionary Envisions More. New York Times. Retrieved from the Web on August 15, 2007.