Originally printed in the September/October 2008 issue of Afterimage.

Posted January 28, 2009

Although the term "avant-garde" may be a relic of modernism to some, it is an appropriate descriptive term for an emerging group of Egyptian artists often referred to in their community as "independent artists." Along Nabrawy Street, a small, gritty alley in downtown Cairo, where automobile repairmen fix cars in the middle of the street and a good cup of coffee or tea can be found for one or two Egyptian pounds, resides a fledgling yet important contemporary arts space: the Townhouse Gallery for Contemporary Art. For many independent artists based in Cairo, the Townhouse Gallery, founded in 1998 by William Wells and Yasser Gerab, has been a major venue and resource in establishing an international voice for Cairo-based independent artists as well as providing a space for contemporary artists from other parts of the world to exhibit and produce work. Wells states that Townhouse has offered "artists an opportunity to enter into the ‘global’ debate that had been denied them by the cronyism that dominated Egyptian representation at home and abroad." (1)

Although the term "avant-garde" may be a relic of modernism to some, it is an appropriate descriptive term for an emerging group of Egyptian artists often referred to in their community as "independent artists." Along Nabrawy Street, a small, gritty alley in downtown Cairo, where automobile repairmen fix cars in the middle of the street and a good cup of coffee or tea can be found for one or two Egyptian pounds, resides a fledgling yet important contemporary arts space: the Townhouse Gallery for Contemporary Art. For many independent artists based in Cairo, the Townhouse Gallery, founded in 1998 by William Wells and Yasser Gerab, has been a major venue and resource in establishing an international voice for Cairo-based independent artists as well as providing a space for contemporary artists from other parts of the world to exhibit and produce work. Wells states that Townhouse has offered "artists an opportunity to enter into the ‘global’ debate that had been denied them by the cronyism that dominated Egyptian representation at home and abroad." (1)

Even though there have been other galleries that sometimes featured experimental or independent artists before Townhouse, the organization has encountered difficulties. Wells remarked,

We have been working against several obstacles and those obstacles happen to be an official art world that doesn’t recognize the work that is being produced by the independent art scene, and that’s a huge problem. We can’t send our posters [or] our invitations into art colleges. We are not allowed to do that. We are not allowed to post them up onto a lot of public institutions because the work that is being produced tends to question. It tends to raise social issues particularly in terms of how Egypt is represented. Images like this aren’t necessarily popular in Egypt. (2)

Photography, video, and other electronic media works are relatively new for artists living in Egypt. According to Wells,

Back in 1998 when we first opened there was nobody showing photography. We were at that stage. You had Sony Gallery at American University of Cairo, which was for documentary photography. But in terms of artists using photography as a medium, the whole culture discouraged it … and you could forget about video.(3)

For the last ten years, however, lens-based media has played a significant role in the cultural production of many independent artists based in Cairo. For example, artist Maha Maamoun creates socially poignant photographs that reflect contemporary life in Cairo. In her series of photographs entitled "Cairoscapes" (2001-03), rather than presenting the viewer with sublime views of Cairo’s buildings and streets, Maamoun captures micro-panoramic views of fragmented street scenes that include snippets of women’s colorful floral dresses as they pass down the street against the backdrop of man-made structures, automobiles, and pavement, providing a moment of escape and relief in a sometimes tough and overbearing city. Maamoun says, "For me, floral print fabrics act as a surrogate for nature in the city and offer a point of release in the midst of its hustle and bustle. These moving gardens are more present and prevalent in Cairo than real nature." (4)

Some of Maamoun’s works are tongue-in-cheek social commentary that examine her concern with contemporary Cairo. In Cairo at Night, part of her 2005 "Domestic Tourism" series, Maamoun presents the viewer with a scenic view of Cairo at night–with fast-moving cars speeding down the highway, tour boats traveling along the Nile, and billboards filling every nook and cranny of the densely populated urban landscape. As one begins to examine the image more closely, however, the repetition of a man’s smiling mouth–that of Egyptian President Mubarak–plastered on every billboard becomes apparent. Playing with the notion of the "Smile of Egypt" campaign, Cairo at Night examines the dichotomy of the "real" versus media-fabricated life of Cairo that the tourism industry wishes to project.

In 2002, photographer Amal Kenawy departed from incorporating Sufism philosophy into her work by tackling more personal subject matter with the time-based installation "Frozen Memory" (2002), a collaborative effort with her brother, sculptor Abdel Ghany Kenawy. The two-room installation examined the loss of identity and self. In the first chamber, a life-sized, translucent wedding-like dress stood upright in the middle of the darkened room. Live butterflies fluttered inside the illuminated gown. Adjacent to the dress, projected static imagery flashed in the background against the wall–primarily of a man lying on a bed appearing to be suffering from insomnia or depression while other abstracted imagery is interwoven into the sequence–possibly acting as a metaphor for unfulfilled desires. The mechanical sounds of the slide projector as well as an eerie soundtrack echoed in the background. In the second room was an actual wedding dress and a video projection of a glass container full of water into which was projected animated imagery. An indistinguishable voice mumbled in the background as the video presented such surreal imagery as a wedding dress constructed by fire and a woman’s face being covered by clay–reinforcing the loss of identity. Surprisingly, Kenawy insists that this is not a commentary on marriage. She says, "In ‘Frozen Memory,’ I grapple with the subject of isolation or alienation experienced by a person while living amongst others in society; I look at how each of us is a mechanical part in society’s churning wheel that turns and turns, never stopping." (5)

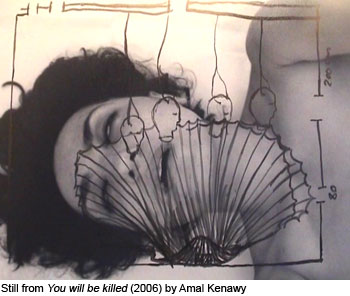

Kenawy’s provocative video You will be killed (2006) was the result of a visit to a military hospital in Egypt built thirty years ago by the British. The visit triggered memories of war and violence in her imagination and caused her to reflect on the current situation within Lebanon and Iraq. Incorporating drawing and photography. Kenawy created a hybrid video animation that presents disturbing, surreal images of a woman’s face trapped within closed spatial elements. Throughout the piece, using stop-motion animation, decapitated and dismembered women are presented to further the idea of senseless violence. The irony that Kenawy’s video depicts is that through violence and death, life begins–such as the crude animation of a tree growing from a mutilated body. This metaphor may not be meant to represent a positive cycle of life but rather the spawning and cyclical nature of violence, how it never seems to stop and is reinvented or reused as a tool to attain or retain power with each generation.

Kenawy’s most recent piece, "Cairo … Eating Me Inside" (2007-08) is a combination installation and performance about conformity and its impact on the individual. On the darkened stage, two diametric images were presented. On the left side, representing the internal, was a video projection alternating between depicting unsettling images of rapidly rotating drawings and a woman with a gun to her head. In front of the projection were lungs dangling from the ceiling, attached to an air compressor so they inflated and deflated to emulate breathing. On the right side of the stage, Kenawy walked in circles along the parameter of the translucent curtain. This represents her external self–the self that the world sees. "We are not able to approach or speak about what is underneath the surface … So there is always this quiet image on the surface and under the surface there’s a spoil … it is about becoming a sacrifice in a societal machine," Kenawy said. (6)

Filmmaker Sherif EI-Azma’s controversial video, Interview with a Housewife (2000) follows a similar path of investigation as to how one can be conditioned by media and society. The piece deals with gender issues and how the media and society define gender roles. By interviewing his mother, an Egyptian housewife, EI-Azma attempts to shed light on the social conditions and gender-related issues of contemporary Egyptian women. EI-Azma states that Interview with a Housewife is important because it:

examines the idea of television, it examines the idea of living with media indoors and how your interpretation of the country is through that television if you’re locked up in the house, like a housewife. And how your inner life becomes like the television programs that you look at or that you’re allowed to look at through national television. (7)

Using television noise as transitions and a blue screen, EI-Azma immerses his subject into a McLuhanian type of environment where the "medium is the massage." When the work was created, it was controversial because of its subject matter, but according to EI-Azma, the "preoccupation of getting away with uncovering social ills is an era of the past. It’s the era of the ’90s. Now we’re in an era where the content is really important, not just the issue … I mean they [the government] have learned over the years that it’s hard to control everything." (8)

In 2003, EI-Azma completed a complex and abstract narrative film entitled Television Pilot for an Egyptian Air Hostess Soap Opera (2003). Using the seemingly cultureless environment of the airplane to explore issues of globalization and identity, the surreal-like film chronicles two entry-level stewardesses as they interact with passengers, co-workers, and superiors, EI-Azma comments, "For me, the airplane is a kind of fictional theater where people are seated, and the relationship between hostess and guest is a completely theatrical situation. But in the back, these small kitchen-like cubicles and bathroom-like cubicles are completely real."(9) The strength of the film is that the airline’s plane and training center is stripped of any kind of national cultural identity other than the women themselves, speaking their native language. The uniforms, the plane’s interior, and the training center provide us with no indication of their geographic location, which may make one reconsider the impact of corporate globalization around the world.

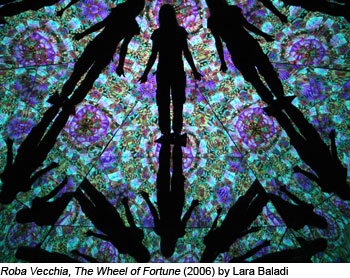

Lara Baladi explores the intersection between fact and fiction as well as issues of narrative. Her installation/sculpture Roba Vecchia, The Wheel of Fortune (2006), is a life-size kaleidoscope in which the participant becomes immersed in a psychedelic environment where rapidly yet systematically changing imagery engulfs the viewer. Instead of using such materials as loose, colored beads or pebbles to generate imagery, she uses images from a trip to Tokyo, as well as other found digital images. The computer program created by Baladi and her cousin then selects the imagery from a database to create stunning visual effects. Baladi, who refers to the images as "digital trash" relates it to fragments of memory, presenting an interesting metaphor on how one may construct and deconstruct memory from our complex personal histories. She states:

Lara Baladi explores the intersection between fact and fiction as well as issues of narrative. Her installation/sculpture Roba Vecchia, The Wheel of Fortune (2006), is a life-size kaleidoscope in which the participant becomes immersed in a psychedelic environment where rapidly yet systematically changing imagery engulfs the viewer. Instead of using such materials as loose, colored beads or pebbles to generate imagery, she uses images from a trip to Tokyo, as well as other found digital images. The computer program created by Baladi and her cousin then selects the imagery from a database to create stunning visual effects. Baladi, who refers to the images as "digital trash" relates it to fragments of memory, presenting an interesting metaphor on how one may construct and deconstruct memory from our complex personal histories. She states:

The kaleidoscope is now looked at as a toy but Walter Benjamin uses the kaleidoscope as a metaphor for talking about history and how we write about history with leftovers and it is like little bits and pieces of trash that is usually seen in the kaleidoscope. From these bits and pieces you actually create a whole constructed linear story of what may have happened before.(10)

Exploring the idea of nostalgic cinematic devices is not new for Baladi. The idea of the magic lantern, an apparatus for projecting images painted on glass with translucent colors, is apparent in Baladi’s eccentric installation, "Fanous El Sehry" (2002). The installation consists of a large eight-pointed star constructed of steel–approximately 23 feet in diameter–and a series of light boxes containing saturated colored images produced from x-ray photographs of a pregnant doll giving birth. As one wanders around the installation, the viewer watches the doll engage in an endless cycle of reproduction. Round and round, one can watch the doll be born, grow up, and reproduce again. The doll may be doing a somersault as she is about to give birth or may appear to be dancing, and in one sad instance, the figure loses her life as she gives birth. The eight-sided star, a symbol of regeneration, is appropriate for the more than 98 feet of imagery depicting the cyclical nature of life. While the imagery is playful and at times melancholy, it begs the question, Is there more to a woman’s life than baby manufacturing?

Artist and Islamic scholar Huda Lutfi questions the notions of identity in regard to gender and culture. Using found photographs and other objects and imagery, Lutfi creates thought-provoking assemblages and collages that question preconceived notions of identity. Lutfi mixes historical texts with imagery inspired by the magical and spiritual iconography of Pharaonic, Coptic, Arab, Mediterranean, Indian, and African cultures. She believes an authentic cultural identity is a myth, and likes the idea of recycling and appropriating imagery because she believes it creates a dialogue between herself and the imagemaker whose work she is appropriating.

Artist and Islamic scholar Huda Lutfi questions the notions of identity in regard to gender and culture. Using found photographs and other objects and imagery, Lutfi creates thought-provoking assemblages and collages that question preconceived notions of identity. Lutfi mixes historical texts with imagery inspired by the magical and spiritual iconography of Pharaonic, Coptic, Arab, Mediterranean, Indian, and African cultures. She believes an authentic cultural identity is a myth, and likes the idea of recycling and appropriating imagery because she believes it creates a dialogue between herself and the imagemaker whose work she is appropriating.

In her mixed-media installation, "She’s putting it on … taking it off" (2003), Lutfi appropriates a photo of a woman with folds of fabric covering her head and torso from Peter Greenaway’s film Prospero’s Books (1991) to create nine almost identical paintings on canvas hung side-by-side on the gallery wall. While the viewer may be unsure about whether the figure is dressing or undressing, the work raises questions about objectification. It is not just about the covering, such as in the case of the abaya, nor the uncovering, such as the concept of the nude or more crass pornography–it is about the objectification common to all human cultures.

These independent artists in Cairo have sparked the interest of many museum and biennial curators in the past few years. Kenawy states:

Recently there has been an increase in global interest in the Middle East and Muslim societies. Some of this interest has been channeled into endeavors that look beyond the stereotypes and images produced by mass media and attempt to discover the reality. This interest has had a positive effect on Egyptian artists as well as artists from the region as a whole. (11)

In the last few years, the independent art scene has become more organized with the formation of an arts council. Wells commented:

Cairo stands out as being a city where artists have mobilized themselves into some sort of a common identity. We have something called the Arts Council Egypt. And it originally started about a year and a half ago, consisting of individual institutions. Townhouse is one of them. There are some studios, the Contemporary Image Collective, the Alexandria Contemporary Art Forum; these were the initial groups … They have come together and realized that they can work together, share resources and have a common platform. (12)

In spite of the growing poverty and cultural obstacles in Egypt, Cairo’s "independent" artists are making their mark on both the local and international art scene. It is through voices like those exhibited at the Townhouse Gallery for Contemporary Art as well as the tireless efforts of such organizations that one is able to better understand the philosophies, issues, and concerns of the people of Cairo that might not normally be shared with the public.

NOTES

1. William Wells, The Project of the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo: Where is Art Contemporary?, publication of presentation at The Global Challenge of Art Museums II Conference (Karlstulic Germany: ZKM Institute, 2007), 2.

2. William Wells at World Art Cities Panel Discussion as part of the 2007 Global Art Forum in Dubai on March 9, 2007.

3. Author interview with William Wells on January 2, 2008.

4. Sonali Pahwa, "Alternative Narratives," Al-Ahram Weekly Online, December 25–31, 2003; see http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2003/670/cu5.htm.

5. Amal Kenaway, "Frozen Memory" Artist Statement.

6. Author interview with Amal Kenawy on January 1, 2008.

7. Author interview with Sherif El-Azma on January 4, 2008.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Author interview with Lara Baladi on January 5, 2008.

11. Amal Kenway in conversation with Geral Matt; see www.amalkenaway.com/GeraldMatt.html.

12. William Wells at World Art Cities Panel Discussion as part of the 2007 Global Art Forum in Dubai on March 9, 2007.